Common .Net Gotcha

Expert Advice from Former Tech Elevator Instructor, Matt Eland

Read along with Tech Elevator Instructor, Matt Eland, as he talks “Common .NET Gotchas” in Software Development.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published to Tech Elevator Instructor Matt Eland’s Blog. You can visit the original post here.

Common .NET Gotchas

.NET Development and C# in particular have come a long way over the years. I’ve been using it since beta 2 in 2001 and I love it, but there are some common gotchas that are easy to make when you’re just getting started.

Exceptions

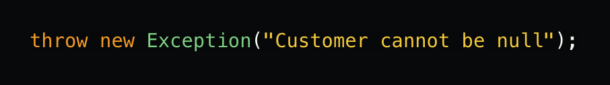

Throwing Exception

If you need to throw an Exception, don’t do the following:

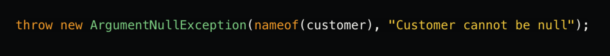

Instead do something more targeted to your exception case:

The reason why this is important is explained in the next section.

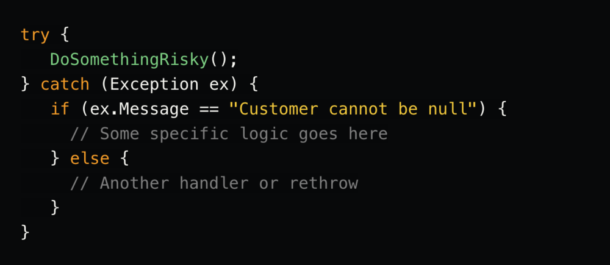

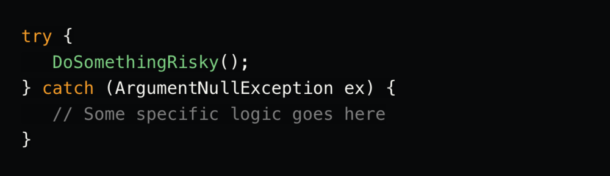

Catching Exception

When a generic Exception instance is thrown and you want to be able to handle that, you’re forced to do something like the following:

Catching Exception catches all forms of Exceptions and is rarely ever what you actually should do. Instead, you should be looking for a few targeted types of exceptions that you expect based on what you’re calling and should have handlers for those, letting more unexpected exceptions bubble up.

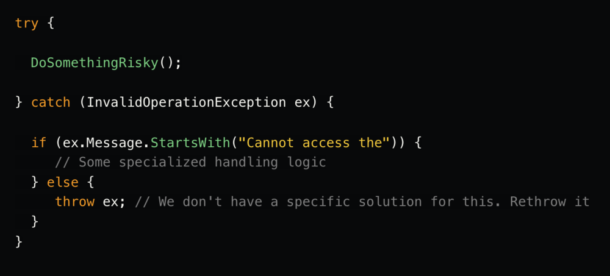

Rethrowing Exceptions

When catching an exception, you sometimes want to rethrow it – particularly if it doesn’t match a specific criteria. The syntax for correctly rethrowing an exception is different than you’d expect since it’s different than originally throwing an exception.

Instead of:

Do:

The reason you need to do this is because of how .NET stack traces work. You want to retain the original stack trace instead of making the exception look like a new exception in the catch block. If you are instead using throw ex (or similar) you’ll miss some of the original context of the exception.

Design

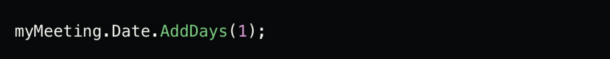

Working with Immutable Types

Some types, like DateTime are said to be immutable, in that you can create one, but you cannot change it after creation. These classes expose methods that allow you to perform operations that create a new instance based on their own data, but these methods do not alter the object they are invoked on and this can be misleading.

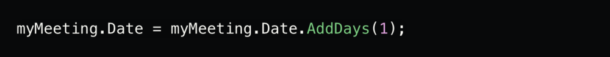

For example, with a DateTime, if you were trying to advance a tracking variable by a day, you would not do this:

This statement would execute and run without error, but the value of myMeeting.Date would remain what it originally was since AddDays returns the new value instead of modifying the existing object.

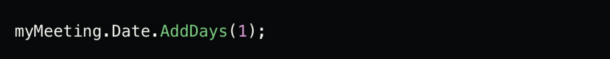

To change myMeeting.Date, you would instead do the following:

TimeSpan Properties

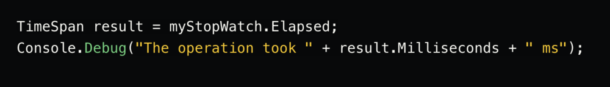

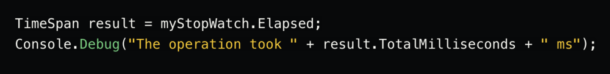

Speaking of Dates, TimeSpan exposes some interesting properties that might be misleading. For example, if you looked at a TimeSpan, you might be tempted to look at the milliseconds to see how long something took, but if it took a second or longer, you’re only going to get the milliseconds component for display purposes, not the total milliseconds.

Don’t do this:

Instead, use the TotalX series of methods like this:

Double Comparison

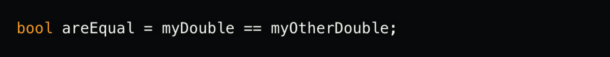

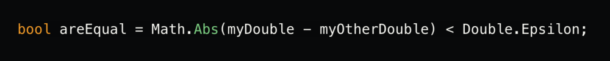

When comparing doubles, it’s easy to think that you could just do:

But due to the sensitivity of double mathematics, those numbers could be slightly off when dealing with fractions.

Instead, either use the decimal class or compare that the numbers are extremely close by using an Epsilon:

Frankly, I tend to steer away from double in favor of decimal to avoid syntax like this.

Misc

String Appending

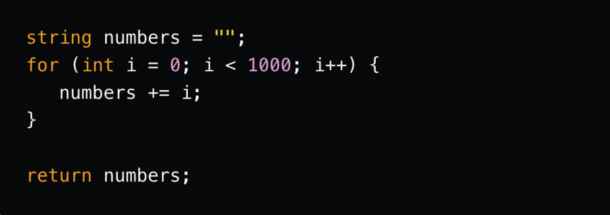

When working with strings, it can be performance intensive to do a large amount of string appending logic, since new strings need to be created for each combination encountered along the way, leading to higher frequencies of garbage collection and noticeable performance spikes.

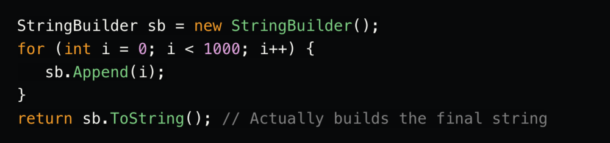

If you’re in a scenario where you expect to append to a string more than 3 times on average, you should instead use a StringBuilder which does techno ninja voo doo trickery internally to optimize the memory overhead for building a string from smaller strings.

Instead of:

Do:

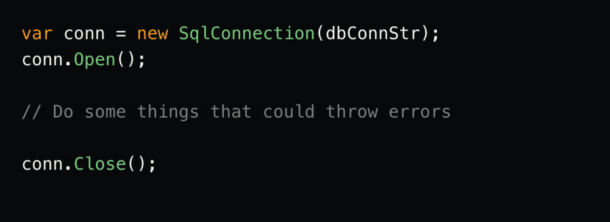

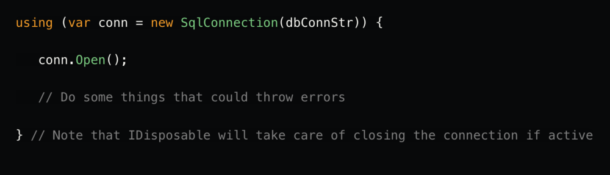

Using Statements

When working with IDisposable instances, it’s important to make sure that Dispose is properly called – including in cases when exceptions are encountered. Failing to dispose something like a SqlConnection can lead to instances where databases do not have available connections for new requests, which brings production servers to a sudden halt.

Instead of:

Do this:

This is the equivalent of a try / finally that calls Dispose() on conn if conn is not null. Note also that database adapters will close connections as part of their IDisposable implementation.

Overall using leads to cleaner and safer code.

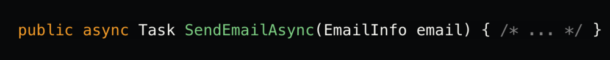

Async Void

When you declare an asynchronous method that doesn’t return anything, syntactically it’s tempting to declare it as follows:

However, if an exception occurs, the information will not correctly propagate to the caller due to how the threading logic works under the cover. This means that any try / catch logic in the caller won’t work the way you expect and you’ll have buggy exception handling behavior.

Instead do this:

The Task return type allows .NET to send exception information back to the caller as you would normally expect.

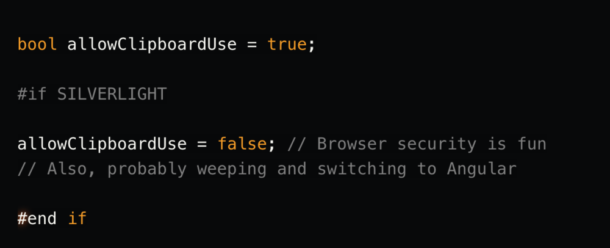

Preprocessor Statements

Preprocessor statements are just plain old bad. To those unfamiliar, a preprocessor statement allows you to do actions prior to compilation based things defined or not defined in your build options.

The correct use of preprocessor statements is for environment-specific things, such as using a library for x64 architecture instead of another one for x86 architecture, or including some logic for mobile applications but not for other applications sharing the same code.

The problem is that people take this capability and try to bake in customer-specific logic, effectively fragmenting the code for allowing it to compile targeting different targets, but by which set of logical rules or UI styling is desired.

This becomes hard to maintain and hard to test and does not scale well. It also makes it easy to introduce errors while refactoring and overall will slow your team’s velocity over time.

Some people advocate for using the DEBUG preprocessor definition to allow for testing logic on local development copies, but be very careful with this. I once encountered a production bug related to deserialization where the development version worked fine every time because it had a property setter defined in a DEBUG preprocessor statement, but deserialization failed in production for that field leading to buggy behavior.

Again, be very careful and lean towards object-oriented patterns like the Strategy or Command pattern for client-specific logic or other types of behavioral logic.

Deserialization

Speaking of deserialization, be mindful of private variables, properties without setters, and logic that exists in property setters or getters. Different serialization / deserialization libraries approach things differently, but these areas tend to introduce obscure bugs where properties will not populate correctly during deserialization.

These are a few of the common .NET mistakes I see people encounter. What others are there out there that I neglected to mention?